I discovered I could learn new things from the pictures .

– Parker, grade 2

From making my trifold, I discovered drawing my animal in its habitat gives lots of information to my reader.

– Fiona, grade 2

My favorite part of the writing was making magic with my painting because it was surprising how my puffer fish moved on a still painting.

– Archer, grade 2

Within our current educational system, it is easy to dismiss art, a subject not tested, as “fluff” or at least as not relevant to teachers’ core mission of teaching “academic subjects” (i.e. those that will be tested). Few educators consider the important role that pictures can play in reading and writing informational text, especially when it comes to teaching our wide range of learners.

The Challenge

Traditionally, when we think of conducting research, we picture reading one or more written texts and taking notes on the information relevant to our inquiry. That is all well and good for those who are comfortable readers. But what about English Learners or others who struggle with reading? How do we make the research process relevant and engaging for them?

Visual Research: Making the Research Process More Inclusive

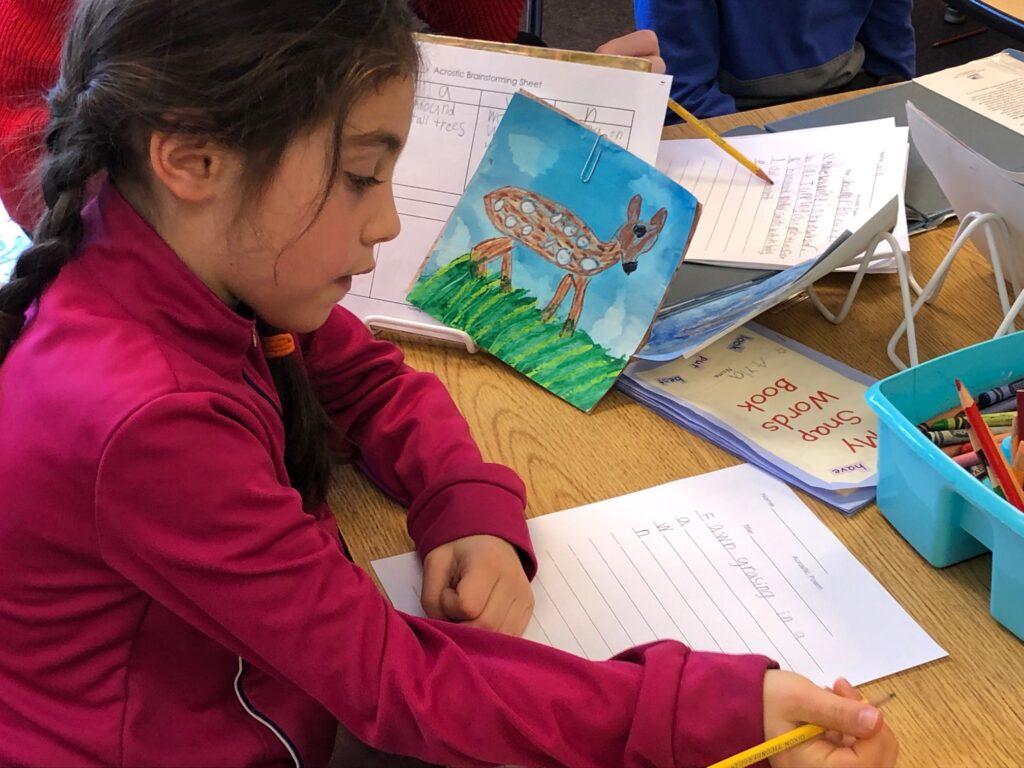

Within the Picturing Writing Research-Based Animal Trifold Unit, rather than ask students to read the text right away, we ask them to conduct visual research. Students “read the pictures” in a fact-based picture book about the animal they have chosen. Reading the pictures is a skill that students have been practicing ever since they were read to as young children. Because pictures offer a universal language, all students can participate in conducting research no matter their reading ability.

Within the genre of fact-based animal picture books, the pictures generally contain a myriad of facts. Some of that information is obvious such as physical characteristics or habitat details. Other information may be gleaned through “close reading of visual text” and drawing inferences. Even the color of the sky, something we don’t often pay attention to when we look at a picture of an animal, can tell us when the animal is awake. Students become detectives, searching for clues within the pictures.

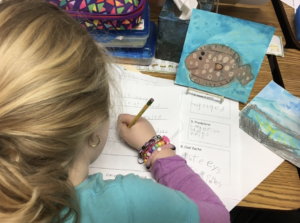

Our specially designed research sheets invite students to read the pictures in their resource(s) for information relevant to the animal trifold they will be creating. They are asked to find information about their animal’s habitat, physical characteristics, how their animal moves, when their animal is awake, how and what their animal eats, predators, how their animal protects itself, etc. In their quality fact-based picture book, most of this information will be embedded in the pictures.

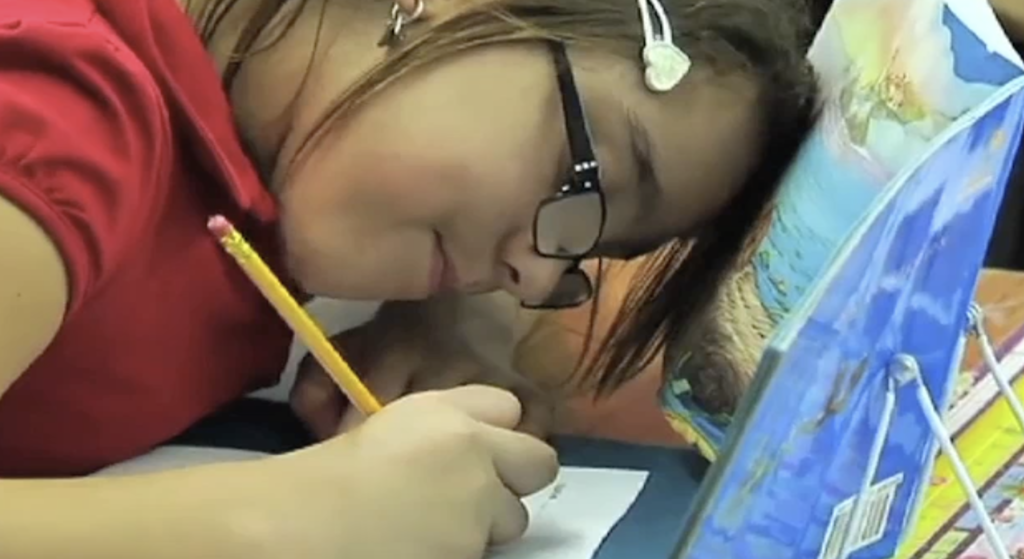

Students read their “visual text” (the pictures in their resource) and jot down the facts they have gleaned. To do this, students practice the visual counterpart to two key reading standards: 1) close reading of text (in this case, close reading of visual text) and 2) drawing inferences. Should they be asked, “How do you know that?” about a fact they’ve jotted down, they will then cite their evidence—yet another key reading standard.

Further Inquiry

While taking notes from reading the pictures, students may develop questions that lead to further inquiry. Whether or not questions arise, the next step in the research process is to read the written text. Depending upon students’ abilities, this can be accomplished in different ways: 1) by individual students reading their own text, 2) by small groups of students who share the same animal, each group having at least one strong reader, or 3) by students reading from multiple copies of the same animal book during their reading group. Additional facts, accessed from reading the written text, are added the research sheet.

One worthwhile activity is to have students jot down the facts retrieved from the written text using a different color writing implement than the one used for writing down facts retrieved from the pictures. This small but important practice allows students to glance at their completed research sheet to determine what kinds and how much information came from the pictures versus from the written text. Whatever the balance, and that will vary book to book, the message is loud and clear: Professionals convey facts in both pictures and words. We see examples of this in fact-based picture books all the time.

A Second Form of Visual Research

A second form of visual research involves sketching. In order to sketch one’s animal, students must practice “close reading of visual text,” now focusing on their animal’s physical characteristics, details both large and small. While drawing an animal may feel overwhelming at first to both teachers and students, there are tricks to that activity, such as identifying geometric shapes or simple familiar objects and then constructing the animal shape by shape, parts to whole. A lesson in sketching is critical to this task as students are going to need to know how to draw and then paint their animals. Sketching, which requires close observation, is an important form of research utilized by scientists and artists alike.

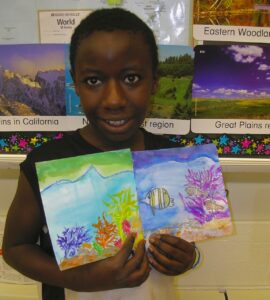

Embedding Facts in Their Paintings

Within the Picturing Writing process, students always create their pictures before they write. There are several reasons for this. Painting first:

- engages and motivates students who struggle with writing.

- deepens students’ thinking and learning even for those who are solid writers.

- allows students to embed animal facts into their pictures thus securing this information to the page before facing the challenges of creating written text.

Creating pictures first before writing using our highly scaffolded Picturing Writing process has been proven effective in advancing writing skills for a wide range of learners.

Then, through the process of transmediation (the translating or recasting of meaning from one sign system to another), students read their paintings to access detail and description. The phenomenon of transmediation has been shown to deepen students thinking, generate new ideas, and create opportunities for reflective thinking (Siegel, 1995). Within the Picturing Writing process, transmediation also fosters vocabulary development, which is key to becoming a strong reader and writer.

Laying Out Fact-Based Written Clues With the Reader in Mind

Once their artwork has been completed, students creating fact-based animal guessing trifolds are given the task of laying out their clues in a way that not only engages their readers, but also keeps their readers guessing. While we often hear that good writers consider their audience as they write, this is a skill that is difficult for most students.

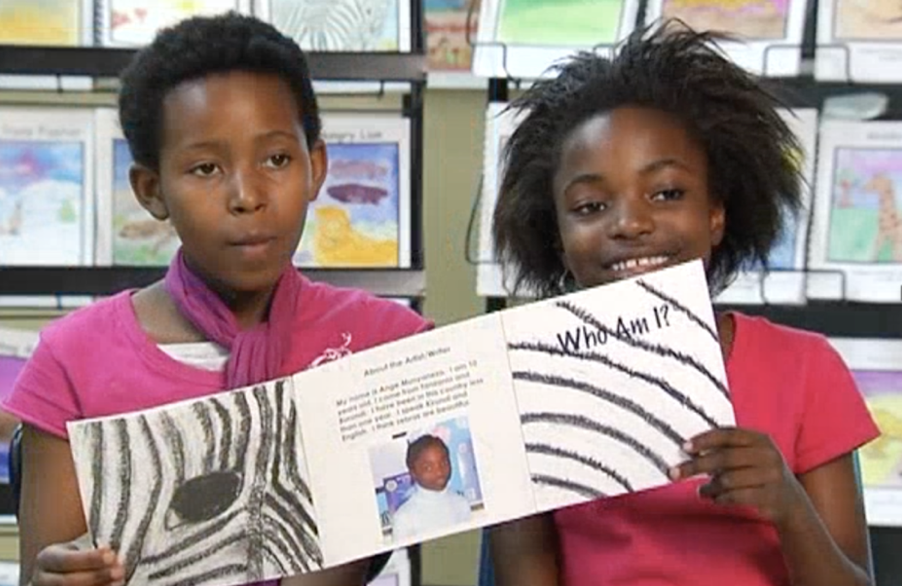

However, in the process of creating a Who Am I? guessing trifold, keeping the reader guessing is part of the challenge and the fun.

For students, that means saving their “give-away clue” for the end. It also means strategically ordering clues starting with the most general glue at the top of the page and then offering more and more specific clues as the writer moves down the page. Even kindergarteners and first graders understand the concept of saving that “give-away clue” for the end.

Discovering the Magic of Bringing Words and Pictures Together

Within the Picturing Writing Research-Based Animal Trifold, students create fact-based I Poems designed to keep their reader guessing until the very end. The second piece of informational writing is generally either a fact-based Animal Acrostic Phrase Poem or a Magic Poem. For younger students, the Magic Poem focuses on using strong, active verbs or verb phrases to describe what the animal is doing. For older students, a fact-based Acrostic Phrase Poem offers another layer of challenge, tapping into another whole skill set. Students must come up with a factual statement that begins with each letter of the animal’s name. When expanding the acrostic form to include phrases or even sentences, students sometime discover the “wrap around sentence” which weaves through more than one consecutive letter of their animal’s name. Students who enjoy puzzles find this type of informational writing particularly fun albeit challenging.

When students include strong, active verbs in either of these poetic forms, they discover that when they stare at their animal painting while their poem is being read, those active verbs can make their animal “come alive.” This “magic trick” (aka simultaneous transmediation or the processing of two sign systems—pictures and words–at the same time) can cause quite a stir in classrooms K on up. After all, who doesn’t want to learn how to make their painting come to life?

Learning How to “Make Magic”

To experience the magic trick is one thing, but to understand how to make magic is quite another. In order to make their paintings come alive, students must consider just how the magic trick works. This involves analyzing just what was occurring when the magic happened? And then determining what key components are necessary to making their animal appear to come alive?

Eli, a third-grader, takes a stab at explaining, “So if you use good words, it creates pictures in your brain, and it makes it look like it’s actually moving.” But what exactly does Eli mean by “good words?” Zander chimes in, “I think my silver dollar words made it so my picture could make magic.” “But what kind of silver dollar words?” I ask. It is Catherine, a fifth-grader, who is able to articulate the answer more precisely: “When I write to my picture, I use many active verbs to make my picture move.” Jeremy, her classmate, adds, “When I find the right words, my picture comes alive.” To readers new to “the magic trick,” this may provide some insight into what Archer, grade 2, meant when he wrote on his About the Artist/Writer page:

My favorite part of the writing was making magic with my paintings because it was surprising how my puffer fish moved on a still painting.

References

Siegel, M. (1995). More than Words: The Generative Power of Transmediation for Learning. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de l’éducation, 20(4), 455–475. https://doi.org/10.2307/1495082